The term “hack” used to denote an unprincipled, untalented news reporter, but journalists have since reclaimed the word use it it proudly now. It’s still used in the publishing business to refer to a journeyman take-on-any-topic type of writer, as opposed to one who specializes in a given area.

The term “hacker”– at least within tech circles – describes a computer programming enthusiast who loves having a clear and complete understanding of the systems s/he works on and enjoys creating clever programs. The layperson’s use of the word “hacker” is more often than not used to denote people who break into computer systems – the preferred term for this sort of person is “cracker”.

While both fields appear to be quite different, there’s much that binds them together these days. Both now work online and both deal with the interpretation, processing and dissemination of information, each in its own way. We even have people who live in both worlds at the same time:

- Adrian Holovaty: Journalist and programmer, he created Django while working at the Lawrence Journal-World and one of the first Google Maps mashups, ChicagoCrime.org (which became EveryBlock), which plotted Chicago Police data of crime locations on a map.

- Jacqueline Cox: Programmer/journalist at the New York Times, she develops data-driven apps for the Times, such as the database of family members for the Haiti disaster.

- Brian Boyer: Self-describe “hacker journalist”, he’s the editor of news applications at the Chicago Tribune

With such an overlap, it was high time that hacks and hackers got together to talk about their respective fields, share ideas and start collaborations. That’s how the Hacks/Hackers meetups got started and spread far and wide. Hacks/Hackers Ottawa had its first meetup at the James Street Pub last night, and I was fortunate enough to catch it, thanks to a timely invite from my fellow Shopifolk Edward Ocampo-Gooding, Ottawa’s open data champion.

With such an overlap, it was high time that hacks and hackers got together to talk about their respective fields, share ideas and start collaborations. That’s how the Hacks/Hackers meetups got started and spread far and wide. Hacks/Hackers Ottawa had its first meetup at the James Street Pub last night, and I was fortunate enough to catch it, thanks to a timely invite from my fellow Shopifolk Edward Ocampo-Gooding, Ottawa’s open data champion.

I took notes during both presentations and present them below. As always, any inaccuracies should be pointed out to me, either via email or in the comments. Feel free to copy the notes and accompanying photos and use them as you see fit!

Glen McGregor, Ottawa Citizen

- We hacks call it “computer-assisted journalism”, which is a bit of a misnomer

- It’s more accurate to call it “data-assisted journalism”

- For us, the really useful old-school sources of data are:

- Databases

- Spreadsheets

- Maps

- The new-school sources of data, which we’re still getting used to, are:

- Tweets

- Geotagged images

- Foursquare

- and really, anything online

- After the Dawson College shooting, I asked the RCMP how many of the type of guns used in that incident were registered in Canada.

- They couldn’t – or wouldn’t – provide me with that information, so I did made a $5 access to information request for that info in the gun registry (we did spend a billion dollars on it, after all)

- One of the interesting things I noticed was that after Dawson College, there was a spike in registrations of one of the guns used in the shooting: the Beretta Cx4 Storm

- My original conclusion was that it was being purchased by “copycats” – people who wanted to repeat the incident elsewhere, or at least found some inspiration in the shooting

- However, after talking to gun owners and enthusiasts, I found that those Berettas were being bought up for fear that they would be taken off the shelves after the shooting

- The lesson here is that even though you’ve got the data, you still can’t jump to conclusions

- Why use data?

- You no longer have to solely rely on statements made by others, attribute a statement to them and take it as fact

- When you assemble the data and analyze it, you become the authority and you don’t have to attribute statements to anyone else

- In getting the data and analyzing it, you’ll find that it uncovers stories that even the stories’ subjects don’t know!

- An example: we were wondering which Ottawa parking patrol officer issued the most tickets?

- When we asked the city, they didn’t know – they never bothered to look at the data in that way

- Another interesting question that arose from looking at Ottawa parking data: where is the most-ticketed parking meter in the city?

- It’s on Lisgar Street, one block west of Elgin

- Why? It’s near City Hall, the Courthouse, a lot of nearby doctor’s and lawyer’s offices, and…oh yes, a “rub ‘n’ tug”

- Looking at the data:

- Confirms the obvious

- For example, most parking tickets in Ottawa are issued in the Market and downtown. That’s what you would expect

- But it also reveals the unexpected

- For example, the third most-ticketed street is Linda Lane. Never heard of it? Neither had I

- It’s across the street from the hospital

- Finding this out led to a larger story about hospital visitors being targeted for parking tickets

- Interviewed a woman who got a parking ticket because she went to the hospital for some reaction to food and had parked outside. She fell into a coma for a few days, but recovered. She had little money and was going to celebrate her recovery with a dinner but couldn’t because the money had to go to a parking ticket she’d received while in the hospital.

- Confirms the obvious

- You get interesting results with mash-ups (the combination of two different data sources to get new revelations – in the old days, this would’ve been called “cross-referencing”)

- One mash-up combined locations of lottery ticket vendors with geographical income data to reveal that poorer neighbourhoods have more people who sell lottery tickets

- An analysis of school suspension data in Florida’s Emerald Coast area showed that black students were suspended twice as often as whites

- Often, this sort of discovery is a jumping-off point for a story

- Although data is very useful, most people can’t connect to it if you simply present it to them

- People, and thus reporters, want a “face” to the story

- Example: when researching New York City elevator inspection data, a journalist wanted to find the elevator that failed the most inspections

- Found that elevator, but used a “face”: told the story of a person who lived in the building where that failing elevator was located; this person was handicapped and effectively trapped at home whenever the elevator was out of order

- People take more interest if the story has some kind of connection to them

- In the story Hosed at the Pump, we looked at gasoline station pump inspection data

- Found that 75% of the inaccuracies were in favour of the retailer

- This sort of thing is a “water cooler story” – the kind we people people will talk about at the ofice, around the water cooler (or wherever people in offices gather on break)

- Another water cooler story based on data: “Flushed with Olympic Pride” water usage during the final hockey game at the Olympics

- Showed spikes between periods and after overtime

- “I’ve written stories on topics like abortion and gun control, but no story I’ve done has received more negative comments than this one.”

- Another interesting data-driven story: frequency of tweets on May 1, 2011, the day before the Canadian election

- One thing I like about data is that it shows that underneath it all, we’re all alike

- A great example of data-driven journalism: Joshua Benton’s and Holly Hacker’s (yes, that’s her real name) Faking the Grade

- It was analysis of the scores from a standardized school test called TAKS, the Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills

- She got the test returns for every student in Texas and subjected them to statistical analysis

- Found cases where the patterns in which students gave answers to this multiple-choice exam were such that they could only be the result of cheating (statistically unlikely results)

- A Canadian angle: the analysis was done with the help of George Wesolowsky, a math professor from McMaster

- Yet another example: A Politician Looking for Funds? Here are Two Useful Addresses

- Article in the New York Times that revealed, with the help of campaign contribution data, which addresses were associated with the most donations to presidential campaigns

- These addresses are:

- 865 South Figueroa, Los Angeles CA (investment management company handling $90 billion in assets circa 2004) and

- 146 Central Park West, New York NY (which at one point or another was the home address for Steve Martin, Steven Spielberg, Demi Moore and Steve Jobs)

- Crime data is also a good source of stories

- “We like local stories…and [crime] scares people.”

- Showed a mash-up of Google Maps and car theft data in and around Ottawa: most car thefts took place around a private golf and country club

- That’s where the expensive cars are

- The bike theft hot zones in the Ottawa area are:

- Carleton

- Downtown

- Lincoln Field

- Fisher / Meadowlands

- Now about that story of the Ottawa cop who handed out the most parking tickets

- He’s John Raine (he’s retired now), and in 7 years, he handed out 72,000 parking tickets

- That’s 50% more than anyone else on the force

- He didn’t want to be interviewed, but by looking at the data, we could find out when and where he typically worked, so I followed him every lunch hour for a while

- Every ticket he issued was legit

- He was just very efficient: he had a system by which he’d walk down a block, identify the violators and then hand out tickets

- He issued them so quickly – “He’s a parking savant!”

- To get a picture of him, we had to send out one of our surveillance photographers

- The City had no idea he was their top guy

- Looking at a table of data, you’ll find that each column is a story, or at least a potential story

- Hackers know that there are lots of ways to present data; hacks don’t know that

- For an example of how to present data well and in a way that’s easy to get, see Politifact and their “Truth-o-Meter”

- Data sometimes comes in forms that don’t look like data tables

- Example: The Slate article Not Sarah Palin’s Friends

- They scraped her Facebook page every five minutes

- Took note of changes, particularly negative comments that got deleted

- This could be done for Canadian politicians as well: half the MPs have Twitter accounts

- Example: The Slate article Not Sarah Palin’s Friends

- Looking for an idea? Try getting your hands on city overpass records

- When it comes to city data, you’ll find it’s mostly maps

- Why? Because they’re non-controversial

- There’s no performance data on a map – most other types data can reveal that someone’s not doing their job, or doing it poorly or doing it wrong

- Lots of municipal activity ends up creating some kind of electronic record of that activity having happened

- Any kind of official inspection creates an electronic record

- Any 311 call creates an electronic record

- Any official disciplinary report creates an electronic record

- Any application for a licence or any other kind of official registration creates an electronic record

- You have to get past the notion that open data is the data that governments give us to use

- Much of this “open data” is there, but they’re not happy to share it

- Often, they’ll cite the mosaic effect as an excuse for not making data available: where anonymized data, when combined with other data, can be used to de-anonymize it

- Keep an eye on the terms of use for open data databases – they seem to change quite often

- The Canadian federal government maintains a licence on its data – “That is crap”

- In Canada, privacy is practically a religion

- In the US, there’s lots of data on sex offenders – who they are, where they live, and so on

- In Canada, little of that data is available

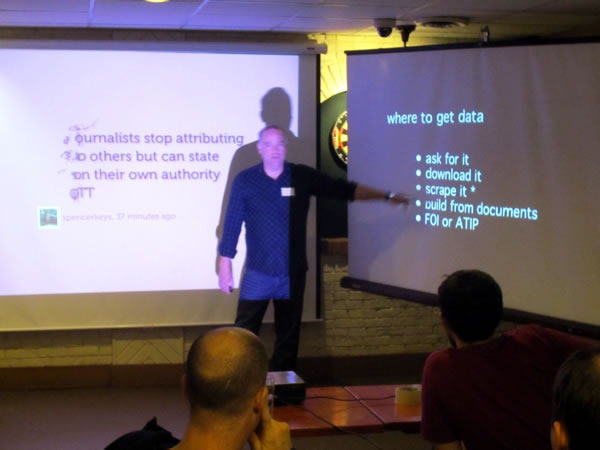

- Where to get data:

- Ask for it

- Download it

- Scrape it

- Build from documents

- FOI or ATIP

- Hacks are good at:

- Discerning news from info

- Interviewing subjects

- Providing context

- Writing

- Offering a big platform

- Hackers are good at:

- Obtaining data

- Processing it

- Analyzing it

- Building better platforms to present it

- Resources:

- nicar.org

- caj.ca

- ire.org

- thescoop.org

- flowingdata.com

- Guardian data-j blog

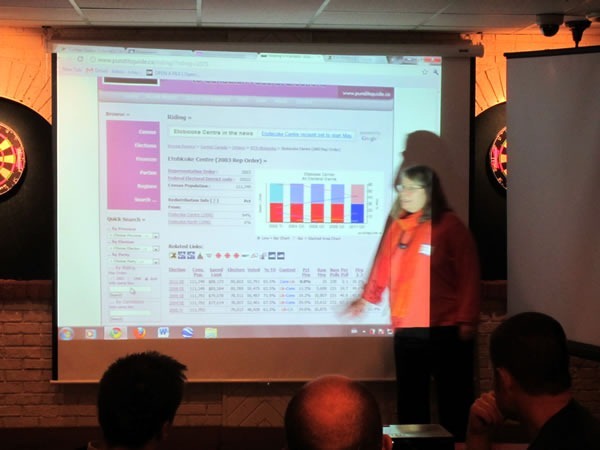

Alice Funke, PunditsGuide.ca

- I used to work on Parliament Hill, but then I took my database programming hobby up a notch and retrained

- A lot of data exists in flat files, and that’s not the way big data is stored

- A lot of data is used for decision support:

- Collect the data

- Ask questions

- In our case, the decision support is for political strategy

- Election data is used for all sorts of things that people don’t think about, including:

- reapportioning seats

- redrawing ridings

- There’s a lot of data downloadable from Elections Canada

- The problem is that it’s not formatted properly

- No unique ID code for each riding appears in the data tables they make available

- There exists a five-character fedcode that’s supposed to uniquely identify any given riding

- Without this fedcode, it’s much harder to make a consistent database, and a lot of additional manual work is required to massage the data

- Without things like unique IDs – so basic to databases – you’d interpret “Peter Mackay” and “Peter G. Mackay” as two different candidates

- So the process of working with Elections Canada’s data is to get the data, then massage it, then put it into a proper relational database

- The data also exists at different levels. For the election, there’s

- The “Who won the seat?” level

- The “How many votes did each candidate get?” level

- The “How many votes did each candidate get for each riding?” level

- “There’s a special kind of hell for Elections Canada because they use .NET for their site, which gives you this giant ViewState hidden variable”

- PunditsGuide.ca was never made for the media, at least not originally

- It was for maybe 15 geeky people like me, and it grew from there

- Interesting fact: Which riding walks or bikes to work the most? It’s not who you’d think:

- 1st place: Nunavut (really?!)

- 2nd place: Trinity-Spadina (okay, that one I expected; I used to live there!)

3 replies on “Notes from Hacks/Hackers Ottawa, May 12, 2011”

[…] This article also appears in The Adventures of Accordion Guy in the 21st Century. […]

Thanks for the comprehensive notes Joey. Hope we’ll see you at the next one? Perhaps we can schedule a musical interlude between speakers?

[…] promised in an earlier article, here are the scans of my handwritten notes from Hacks/Hackers […]